Stupid Internet

Symptoms

All we do in modern society is treat symptoms. Every problem gets a bandaid.

Most of the time the answer is pills:

Sad? Pills. Can’t focus? Pills. Back pain? Pills.

But there’s also:

Bored? Snacks. Shy? Alcohol. Lonely? Tinder. Empty? Alcohol.

Anything to distract us from the root causes of our misery, of which there are not so many, and which are not so complex.

Just as it was surprisingly easy to define “useful artistic communication” when you’re a revolutionary humanist, being politically uncompromising leads us to the following:

Q: What is the root cause of our individual suffering?

A: a large proportion of humans are not able to meet their own basic needs.

(We could argue all day on how deep or true this is but I’m going to take it as granted for the purposes of this essay series, so feel free to leave if you don’t like it.)

Revolutionary art consists of trying, through an infinite variety of means, to convince others of the above. And that message is a bitter pill, and will only be accessible in certain ways, at certain times, to certain people.

Anti-revolutionary communication, which I won’t call art, but which we could call “modern entertainment”, has only one purpose: to sell as much as possible. But to do that, it reduces its appeal to the lowest common denominator and makes itself as accessible as possible. This means it will always be easier to spread than art. It isn’t trying to disagree with the purpose of revolutionary art as stated above, but making something as appealing as possible makes it simple, and revolutionary ideas are not simple. What sells well is individual distraction, and what sells well and widely is simple individual distraction. So we can say that, as opposed to the above, modern entertainment has as its driving force:

Q: What is the root cause of my individual suffering?

A: I’m not enjoying good enough stuff.

Tired from work? Watch a show.

Feeling down? Buy a new phone.

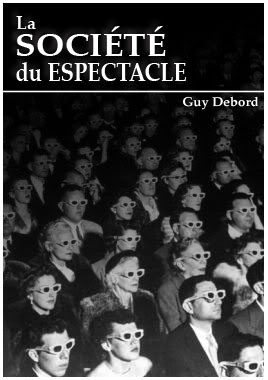

As I mentioned in the intro to this essay series, Guy Debord’s Society of the Spectacle is an amazing treatise on the process by which capitalist culture evolves. The rest of this essay will be inspired by Debord’s ideas, and in support of my overall series thesis (which you can read in the intro if you need a refresher). But to keep things simple, this is the idea I’m going deep on in this essay:

Capitalist culture reproduces itself by transforming authentic artistic expressions into mass-marketable drivel, and the way to resist this process is to:

- deliberately make art hard to categorize by contemporary standards, and

- deliberately consume entertainment from the past rather than the present.

Society of the Spectacle

At the risk of getting too deep into theory, I want to share my understanding of part of Debord’s work, since it’s not an easy work to follow, and any two readers of it will probably end up with different ideas. In fact that’s kind of the point, for reasons that should become clear shortly.

Debord talks about the spectacle as an abstract, mediating force that is all around us, of which we are a part, and through which we see the world. Without getting too specific about it, he nevertheless seems (to me) to be describing a process in which this force corrupts anything that is not a part of it. He calls it something like “the subsumption of X by the spectacle”. The spectacle is not capitalism, since it describes a social force more totalizing than finance by itself, but I think it’s a useful (over)simplification to think of Debord’s point as “capitalism eats us”.

He explains how the drive to make money is so powerful, it tends to subvert revolutionary tendencies. So when someone makes a work of art for the purposes of revolution (against capitalism, say), and that work really speaks to people because of its revolutionary message, rather than fight the work, the money influence buys the work. Or worse yet, agrees with it, and then subtly, insidiously changes it, repackages it, and sells it as far and wide as possible.

Some examples from earlier parts of this very essay series might help.

The revolutionary part of Garden State, the movie, is the meditation on life, the existentialism. Garden State came on the heels of the grunge era - the 90s were a great decade for existentialism. A lot of dark feelings were being explored by the subculture, even as capitalism itself was hypernormalizing. Garden State then took these ideas and mass marketed them. It reduced them to a romcom to make the story more appealing. The cheesy ending makes a mockery of anything useful that could have come out of the movie, of the ideals of grunge. The movie still appeals to people raised in the 90s because of existentialist concepts, which is to say, for revolutionary reasons, but when it counts most, at the end of the movie (and in plenty of places throughout), the punch gets pulled to appeal to a wider audience. The movie sold out.

Or from a musical perspective, hopefully it’s now obvious that everything in the transition from African music to easy-to-sell western music, in which by denying our roots we make something more mass marketable, is a description of the spectacle embracing what helps people and subverting it into something that anaesthetizes instead.

Hopefully you’re getting an idea of my point with respect to Debord’s work. The operations of capitalism turn art into entertainment, and in doing so tend to reduce the complexity of communication dramatically. In fact we should add that:

Cheesy is when you drop nuance and complexity in an appeal to the lowest common denominator.

Now take this process and put it through the internet.

Stupid Internet

The internet can be a useful vector for spreading revolutionary ideas but it’s not a particularly good or evolved vector for such. Difficult ideas work better with high bandwidth, complex mediums - like a book or a conversation. The internet works best for low bandwidth, simple mediums - like social media.

By being hyper accessible and enabling instant publication, the internet forced capitalism to cause our culture to evolve ever more in favor of speed and simplicity. The context of a facebook meme only maintains relevance to its creator for a short time, before it gets either lost or changed in the swirl of subsequent posts. The big money on the internet today goes to those who are relevant in the moment, which gets harder and harder as the internet grows and speeds up.

The internet has also sped up and hypercharged our ability to categorize. Algorithms matching you with the perfect content are commonplace. But those algorithms work best when you, and the content you consume, can be bucketed into efficient, predictable categories. And even as those algorithms improve at long-tail hyper-specific recommendations for each person, they in turn induce us to accept that we are the person they construct. We sell our identity in return for tailored content.

Can revolutionary art work this way? At first glance it seems like it’d be helpful to have hyper-targeted leftist messages to convince each person in the way that would most connect with that person - but I don’t think this is possible. The spectacle has evolved the internet into a medium for simple distraction, while revolutionary art will always entail concentrated discomfort. The internet’s mechanisms of communication, and especially the hyper-targeted ones, are built specifically not to revolutionize.

Defence Mechanisms

My point about defying categorization in the present is that it’s not enough to just say “I want my art to be revolutionary, so I’ll write about helping others”. There are lots of artworks about helping others that are easily categorized, and as such they are easily subsumed by the spectacle.

Say you write a song about stealing bread from the supermarket for the beggar outside. Even though this revolutionary message will probably touch some people, you could still run into a trap. You think, “I want my message to spread”, so you make the song pop-ey and accessible. By doing so you hurt your aims, rather than help them, because you’ve “contextualized” your piece among other pieces that lack your revolutionary message.

Even if your words talk about stealing from the rich to give to the poor, your context says, “like other stuff that sounds like this, this song will help distract you”.

In the case of music the solution is as simple as changing some (even subtle) parts of the instrumentation to be less pop, to defy that categorization. This sends a different message to the listener, specifically, “listen closely, because you don’t know what’s coming”, which is necessary in this case for communicating difficult revolutionary ideas.

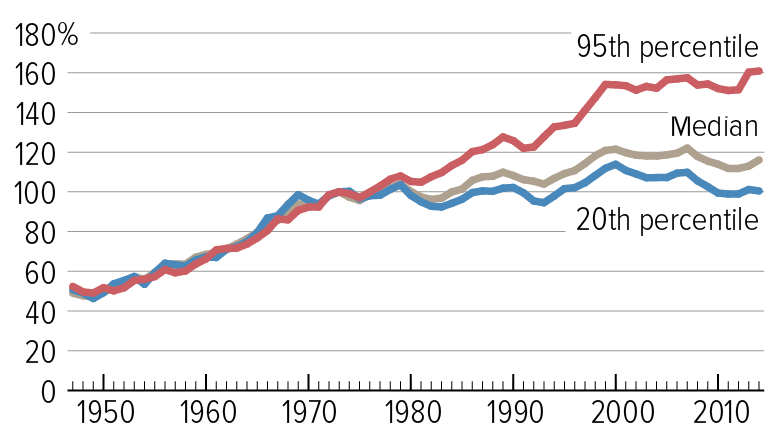

In the case of social media, if you share a meme that directly supports a revolutionary aim, like, say, a picture of a map denoting income inequality across the globe, or a graph showing income inequality in the US, you are running across the same pitfall. This meme is easily categorizable, in this case as “a leftist meme”. Even though nobody is trying to charge money for it directly, you’d better believe that it’s being capitalized and subsumed as we speak - all the leftists on twitter or facebook who are sharing it are also incidentally watching ads and sharing their browsing data with the platform. And being easily categorizable as a “leftist meme”, most non-leftists are going to ignore it, or be algorithmically excluded from seeing it in the first place. So I think in this case the remedy is to depend less heavily on directly copied images, to try to be more creative with short-form revolutionary messaging online, to think about your audience, and to use abstract and esoteric humor to spread the same message that the graph would have. Harder to categorize, harder to ignore, harder for the algorithms to know what to do with.

I think for sure Debord wrote in a deliberately obscure style for a very specific reason - if you make your prose easy to follow, you make it easy to buy. As soon as something has mass appeal, it becomes a target for spectacular subversion. Writing in tautological poetry (Debord) or dense theory for example makes it harder for someone to grasp the point well enough to work the magic of spectacle on it. Or maybe, the goal of revolutionary writing should be to make understanding the idea equivalent to agreeing with it (Marshall McLuhan and I think this sentence should be its own essay, so feel free to ignore it if it makes no sense).

I read the news today oh boy

This isn’t to say that there won’t eventually exist categories for everything we make, even if we are actively avoiding contemporary categories as we’re making things. That’s ok; you can’t avoid categorization, or the spectacle, forever. In fact, by now the evolution of our culture is precisely that process by which artists avoid categorization by the spectacle, and then the spectacle forms new categories for the most popular of these artists.

The goal is only to avoid categorization in the present. The spectacle as it is right now is what’s dangerous - all of our dread at the prospect of the suffering of the billions, and dread that we could easily fall into that camp, is just barely being covered up by an ever-evolving system of distractions that are tailored to precisely counteract the current moment.

In other words, the absolute best, quickest distraction for each news article is the TV show or movie that came out the same year or even week. Migrants being murdered in ICE detainment? Avengers: Infinity War. The mechanisms by which this works are varied and we don’t need to illuminate them all, but I’m not saying there’s a global conspiracy of deliberate distraction. Rather, it’s an illusion or spell that we (the society) cast on ourselves.

- Most people want to believe that everything is fine.

- They buy things that support that belief.

- The best sellers are the entertainments that provide the best distraction.

- Capitalism evolves to reward the most effective distractions.

Add on the speed at which the internet moves and my point becomes clear - capitalism has evolved to provide a timely defence against every bad news article in the form of an extraordinarily distracting piece of entertainment.

To defend against this on a personal level, then, all you have to do is not consume contemporary entertainment. You don’t even have to avoid entertainment altogether; all you have to do is go back in time. The farther back you go, the less anaesthetizing effect the entertainment will have. The entertainment of the 90s was developed by a capitalism that had evolved to distract citizens of the 90s. We are not them. And in fact I think a by-product of the internet requiring such quick publication is that even though the distracting effects of entertainment are stronger than ever, their historical contexts are more narrow than ever. Try watching a show from two years ago. They’re mostly bad, even the ones we thought we liked then, because they no longer provide the distraction from global suffering that we’re all aching for, and they aren’t really good for anything else.

Anyway, hopefully that provides a ray of hope. The internet’s narrow historical context is a weakness that can be exploited. That’s why I’ve identified this idea of “defying categorization in the present” as a helpful and specific form of revolutionary praxis.

The next and probably last essay in this series will be about the utopia of the future through the lens of the Dad Joke, and I hope to see you then.

With love and anger,

Eli