Tradition and the end of art

The point of this essay is to prove a small part of my overall theory of revolutionary art that I’ve been developing over the last few pieces. As a reminder, that theory looks like this:

IF you care to live in a more equitable society,

AND you make and use art to approach that goal,

THEN that art must bridge the traditions of the past with the utopia of the future while defying categorization in the present.

TRADITION

Right now I want to talk about the “traditions of the past” part of the above “THEN” clause. That’s it. I’m going to spend an entire essay to try to defend four words, using music as my lens. So I guess this’ll be a little bit of a digression, because from a purely theoretical perspective I don’t think we need a whole essay for four words.

I would just say something like:

Tradition and history are what make our cultures unique. Without that, we trend ever more towards homogeny, which is a preview of the coming heat-death of the universe. Homogeny, and its mirror twin chaos, are the ultimate evil. All of conscious existence lives in that interstitial zone between the two, that complex layer of signal and meaning. The fact that advanced capitalism seems so driven to mass-marketize every piece of entertainment is just further proof that advanced capitalism is the death-knell of our entire way of life as a species.

Tradition in Music, in entertainment

But since we’re here, let’s talk about that in a bit more depth. Specifically, let’s look at that process of mass-marketization from a historical and financial perspective.

Why does advanced (and also regular) capitalism seem to need to homogenize culture? What is the process by which that happens? How can we resist it, or even just tell the difference? And, since this is in an essay series about “cheesiness”, how and why does mass-market entertainment lead to increased levels of cheese?

Cumbia and Reggaeton

This was a really helpful article about Cumbia music, if you’re curious. I have spent a lot of time in South America, and I really like the sound of Cumbia - specifically, the rhythm. From the above article:

The most discernible element of Cumbia is the double beat played on maracas or a shaker-type instrument. This gives the rhythm its momentum, it’s as if the double beat is pushing you towards the end of the song. Another common ingredient is for a constant, single beat that keeps time thoughout the record.

That squares with my experience. Nothing else has a beat quite like that. Not that other beats are so very different, but there’s something special that lives in that very small difference.

Here is Totó la Momposina, a famous artist who has been keeping traditional Colombian music alive for decades. This is a popular and haunting track about a fisherman. It’s also slower than a lot of Cumbia, which makes it easier to hear the beat. You can hear 3 (or more) distinct rhythmic elements that correspond to those mentioned in the quote above. There’s the slow clapping that provides that “single beat”, the maracas which give you the double beat (pah pah PAH, pah pah PAH), and a more complex drum pattern which plays with the double beat.

To me these layers of complexity are what makes the music interesting. The different rhythms interact in ways that capture my attention and imagination. And, like the quote above mentions, the double beat pushes me towards the end of the song, maybe sort of like a fast-paced plot in a movie.

The blues

Historically speaking, we probably have the influences of African slaves to thank for Cumbia’s beat. According to the article linked above as well as other pieces I’ve been reading while researching this, it was the combination of African and South American culture that led to the complex situation above. Does that story sound familiar to you? If you live in the US it probably should, since that’s exactly what happened here with the blues.

It's generally accepted that the music evolved from African spirituals, African chants, work songs, field hollers, rural fife and drum music, revivalist hymns, and country dance music.

I think similar to Cumbia, what makes early blues so special is the complexity. In this case, of the rhythm that the guitar picks out, as well as the plaintive tone and meaning of the lyrics.

Here we go back a little farther. What I’m interested to point out here is how similar the two pieces are. Same scales, similar melodic structures, similar rhythms. Ed Kopp’s “generally accepted” from the quote above can’t be too off the mark.

Africa to America in the 21st century

So we’ve established this trend that explains a huge part of American (both North and South) musical tradition - the influence of African culture. I’d go farther to say that most of what makes all of this hemisphere’s music so good comes from Africa. Because I’m sure you know the next part - out of traditional South American music, reggaeton, salsa, bossa nova. Out of blues, jazz and rock! And you can still hear the influences so very clearly. Here’s a famous (the most famous) reggaeton track:

The beat is similar to the first Cumbia track I embedded above, but with significant differences. Instead of three fairly simple rhythmic elements it now basically has one more complicated one - a drum kit. And instead of the driving double beat that keeps us engaged, it has the now iconic reggaeton beat:

PAH, pah-pah boom pah, PAH, pah-pah boom pah

And that has made all the difference. If you listen back and forth between Cumbia and reggaeton what you’ll notice (besides a completely different subject matter) is the extra beat or two in reggaeton. There’s at once less complexity and less space for the rhythm to breath, but the sound is much busier, more filled in.

Thievery Corporation

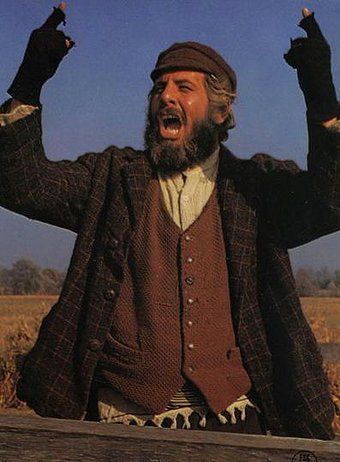

Here’s Elvis, that famous thief of African and African American music. This song has some of the elements of blues that we heard above, but none of the sadness. The guitar’s rhythm and melody doesn’t drone or wail, it bounces. The lyrics, while about something ostensibly sad (being in jail), make light of it. Elvis took art filled with a real and necessary darkness, stripped out that darkness, and sold it to the public as something fun at a huge profit.

By changing the music in this way, we neuter it - we specifically take out the unique elements that remind us of our hemisphere’s African slave trading history, the elements that carry the earlier musical tradition. Yes, it reminds us all of something horrible, but it’s also a unique and beautiful form of music, and something we could learn from. Contemporary evolutions to art have had the effect of denying the traditional influence. Even worse, of denying it while simultaneously benefiting from its former presence. Because there is a huge benefit here - by stealing pieces of the past we make entertainment interesting, which is necessary if we want to sell anything, and by ignoring the sadness in our history we make entertainment more palatable, which means we sell more. Somewhere in the last century we swapped depth for spectacle.

In the Garden State essay I concluded that cheesy is what happens when you deny the darkness around you, which seems to yet again be the case. Here we can add that from a commercial perspective:

Cheesy is what happens when you deny your traditional roots in order to make something more mass marketable.

Thanks for sticking with it. Feel free to read Part 3 of this series, which is concerned more directly with how to avoid the pitfalls of the modern entertainment industry while still being entertaining.

Through thick and thin, Eli